Influencers & elections: An Eastern European campaign blueprint

A brief empirical analysis of an influencer marketing campaign from November 2024 for the presidential elections in Romania

Catalina Goanta

11/17/20245 min read

In 2024, political campaigns can't seem to live without influencer marketing. In the United States, the latest elections were deemed 'the first influencer election' and much has and will continue to be written about the effect of parasocial relationships and social media around this event. Other parts of the world are not getting as much attention, although in many ways there may be interesting parallels (e.g. low trust in government) but also diverging features of the political debate that can reveal other sides of political advertising practices. One of these examples is the upcoming Romanian presidential elections. To be held on 24 November 2024, the elections have been riddled with scandals about the transparency of advertising, particularly by the governing parties, said to have spent around €9 million in one month for (generally non-disclosed) television advertising.

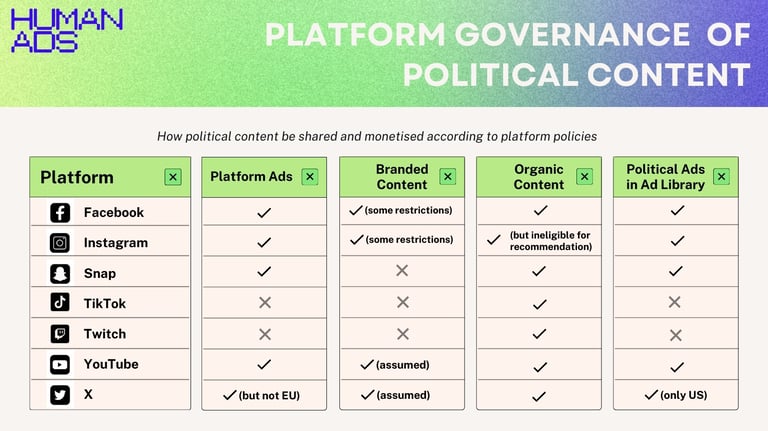

As expected, social media has also been an advertising battleground. Although social media platforms are generally converging towards limiting either the reach or the opacity of political advertising and even political content (see Figure 1 made by our media expert Taylor Annabell), it is often unknown whether and to what extent such content is moderated. Particularly in countries where content moderation might depend on specific languages that are less represented institutionally with the social media platform, political advertising, especially in its branded content version, can live a happy life on the Internet. That is until its availability is noted by other content creators (such as Pleiǎr) who operate as watch dogs and start raising signals of legality and morality.

Influencer marketing & elections beyond the US

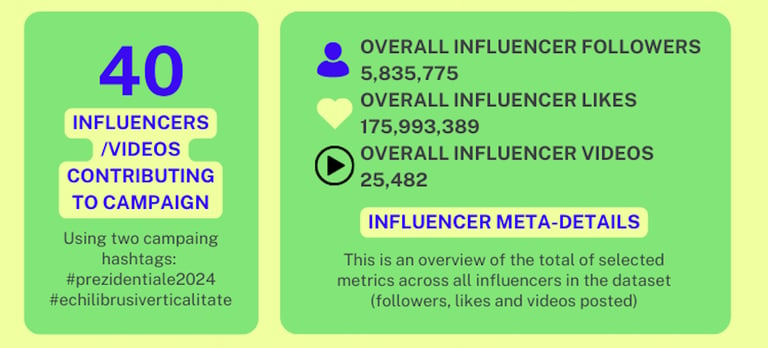

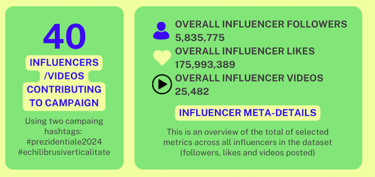

In the past week, a TikTok influencer campaign came to light in the context of the Romanian presidential elections, which is said to have been posted on an influencer discovery platform, allowing influencers to engage. No information has been made available about the advertised rates. What is, however, available, is the TikTok data which can easily be collected using the campaign hashtags: #echilibrusiverticalitate and #prezidentiale2024. The cooccurence of these hashtags, as well as the structure of the videos (which will be elaborated on below) are signals which can lead to a confident conclusion that they descriptors of a political advertising campaign. Using Apify, I collected the videos using these hashtags in the past 10 days (collection date 17 Nov 2024), and collated some numbers to get an overview of the general characteristics of the campaign. I have labelled the 270 results manually and ended up with 40 videos made by 40 influencers. The total number of followers across these 40 influencers is almost 6m, their total number of numbers is almost 176m, and the total number of videos they ever posted is 25,5k.

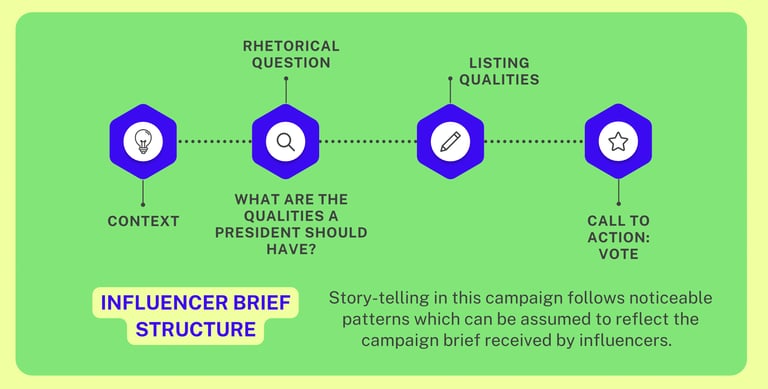

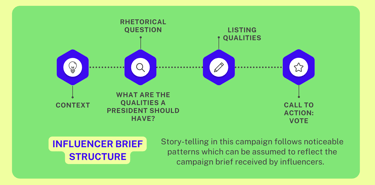

The 40 videos had a similar narrative setup, very likely reflective of the brief shared on the influencer discovery platform:

Context: starting the video with a reminder of the elections, potentially emphasizing the important societal impact of the moment;

Rhetorical question: asking the audience to reflect on the qualities of an ideal president;

Listing qualities: answering the question with a list of qualities (e.g. self-made person, honest and without corruption scandals, patriot, English language proficiency);

Call to action: go vote for the person you think has such qualities.

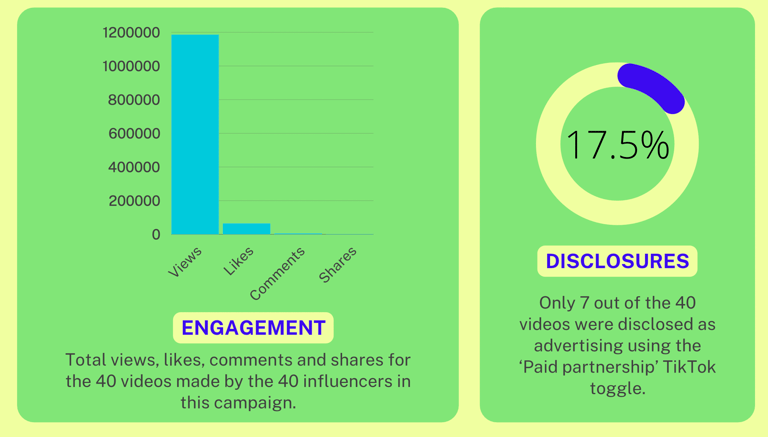

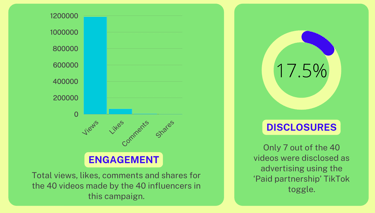

This narrative setup raises some questions about who could be behind such a campaign. On the one hand, if it's the team of one of the candidates in the race, then perhaps not specifically mentioning who audiences should vote for is a strategy of making the campaign more authentic and less linked to a specific name (also for public controversy avoidance). On the other hand, the way in which influencers interpreted the brief does not really make it clear which potential candidate it could be (a handful of the candidates could potentially fall within these criteria - especially the English language proficiency criterion discards a large number of candidates, but not all). It can of course still be possible that the campaign was initiated by a civil society organisation or other actors not linked to the candidates. Since this advertising remains largely undisclosed (7 out of 40 videos include a paid partnership feature), and there is absolutely no reference to who paid the ad, it can be assumed that the organisation behind the campaign did act with some degree of intentionality of hiding its identity.

Some interesting findings:

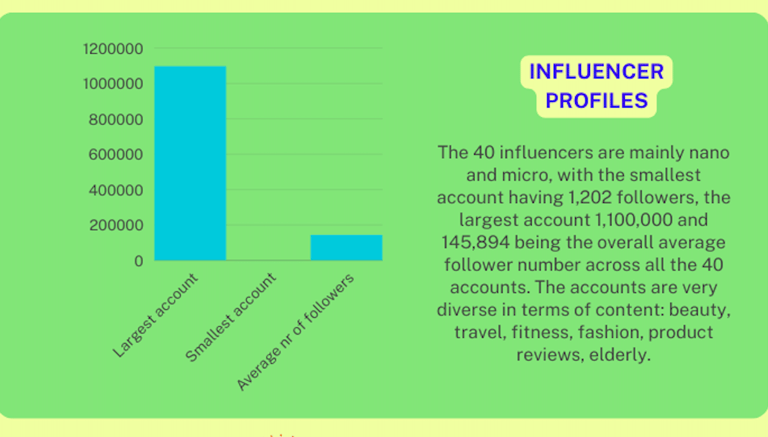

the diversity of influencers participating is very high: from creators making content about fashion, beauty, travel, fitness, to vet students and grandmas;

the largest account has 1.1m followers, and the smalles 1,202. The average of all 40 accounts is 145,894 followers;

While the total views generated by the 40 videos within around a week reaches almost 1.2m, the engagement is pretty weak: 66,196 likes, 5,765 comments and 1,632 shares.

Not captured by the data but based on first observations: the comments of the younger influencers will often feature questions about advertising disclosures, showing some degree of awareness of the audience of such problems. It can also be that the comments are not left by 'fan' followers, but are a result of the coverage by the content creators who started discussing the topic. For older demographics, disclosure discussions generally lack, and people often share their views about who they would vote for, taking the call to action seriously;

A lot of creators covering this topic were referring to the 'hundreds' of videos and/or influencers available on TikTok with this hashtag. However, I was not able to find these videos. The best explanation I have is that for reasons beyond my understanding, TikTok bundles hashtags based on partial word matches and thus also added e.g. 'vertical farming' videos to the #echilibrusiverticalitate hashtag query. This exercise is particularly important to filter out the false positives with some basic manual labelling. One caveat is also important: the scraper did not get all the videos that can be manually retrieved. Some of them fell outside of the queried date (more than 10 days prior), while for some others I have no other explanation than the fact that the scraper had some issues (and if you think the TikTok API is better, you're wrong).

Going back to the point of content moderation, TikTok says it does not allow for political branded content, yet the videos still stand (and also in spite of some users stating in the comments that they had reported some of the posts).

Influencer marketing & the Romanian elections of 2024

Conclusions

While political influencer marketing might become increasingly ubiquitous, since there are a lot of grey areas regarding the disclosure of political advertising by influencers (as Giovanni De Gregorio and I wrote here), it is often very difficult to identify when a political post is sponsored, and most importantly by whom. This overview gives insights into how a (rather basic) influencer campaign looks like in political marketing, and who gets involved in such an action. Overall, although a very important scientific disclaimer is that none of the numbers above can establish a clear impact of these videos on those watching them, given the public criticism and some of the reactions in the comments, this campaign seems to have been a bit of a flop. TikTok may be a cradle of influence operations, but this one is just not it: such campaigns fail to mimic the authenticity needed for more subtle manipulation. Even so, TikTok should better start enforcing its own content guidelines, especially when it comes to asking political advertisers to identify themselves.